Improving Africa’s orphan crops and eradicating stunting in children

UC Davis is partnering with Mars, Inc. in a global plant-breeding consortium that is fighting malnutrition and poverty in Africa by improving the continent’s traditional food crops. These “orphan” crops have been largely ignored by science because they are not internationally traded commodities, but are the food crops grown in the back gardens of the 600 million people who live in rural Africa.

The initiative was inspired by a presentation by Christine Stewart, assistant professor of nutrition at UC Davis, which highlighted the global issue of stunting — a medical affliction resulting from chronic malnutrition that affects a staggering 39% of children in the developing world, and over 130 million children in Africa alone.

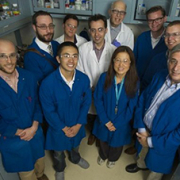

The African Orphan Crop Consortium — conceived by Howard Shapiro, a senior fellow in the  College of Agricultural & Environmental Sciences at UC Davis and the chief agricultural officer at Mars — has chartered an ambitious goal to map and make public the genomes of 101 indigenous African food crops. The genomic data gathered on crops will help plant breeders improve the nutritional content, productivity and resilience of Africa’s most important food resources.

College of Agricultural & Environmental Sciences at UC Davis and the chief agricultural officer at Mars — has chartered an ambitious goal to map and make public the genomes of 101 indigenous African food crops. The genomic data gathered on crops will help plant breeders improve the nutritional content, productivity and resilience of Africa’s most important food resources.

The consortium brings together experts from Mars, UC Davis, and a wide range of researchers, industry groups and policymakers. Together, collaborators have contributed about $40 million of in-kind support to the program.

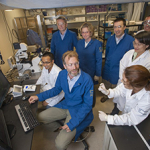

UC Davis has developed an intensive, hands-on curriculum for the consortium’s African Plant Breeding Academy and its state-of-the art genomics laboratory hosted by the World Agroforestry Centre in Nairobi, Kenya. There Africa’s best plant breeding scientists and technicians are being trained to use the latest equipment.

By the end of 2016, more than 50 scientists will have graduated. By July 2016, the group had sequenced 26 whole genomes, resequenced 13, and provided transcriptomes for 21.

“Globally, only 57 plants have ever been genetically sequenced,” Shapiro notes. “The African Orphan Crops Consortium is adding another 101. Graduates of the Academy are professors and heads of research institutes at the top of their game. They now have the ability to make decisions about plant breeding faster, which will lead to higher yielding and more nutritious plants. All of this is happening to benefit some of the poorest people on the planet’s most malnourished continent.”

Through this program, UC Davis faculty travel to Africa and are expected to train 250 breeders over five years. Graduates are already becoming active partners in the orphan crop effort.

Daniel Adewale, plant breeder with the Ondo State University of Science and Technology in Okitpupa, Nigeria, graduated last year. He is using the skills he learned to improve the African yam bean, increasing its essential amino acid content and reducing its cooking time. “By helping breeders improve these forgotten crops, I believe the African Orphan Crop Consortium will cure malnutrition in Africa,” Adewale said.

Daniel Adewale, plant breeder with the Ondo State University of Science and Technology in Okitpupa, Nigeria, graduated last year. He is using the skills he learned to improve the African yam bean, increasing its essential amino acid content and reducing its cooking time. “By helping breeders improve these forgotten crops, I believe the African Orphan Crop Consortium will cure malnutrition in Africa,” Adewale said.

The group collaborates with researchers all over the world, and all of its sequence information will be posted to the internet and offered free to anyone, on the condition it not be patented. “Because we share all our information, we can build on each other’s research,” said Allen Van Deynze, professional researcher with the UC Davis Department of Plant Sciences and a founding member of the consortium, who visits Nairobi each year as part of his commitment to teaching in the academy.