Instead of graduating and jumping straight into the workforce, some enterprising grads are forming companies with ideas and innovations they developed at UC Davis. John Bissell (’08) helped develop a method for creating more sustainable plastic as an undergraduate studying Chemical Engineering. Tom Shapland (’07, M.S. ’11, Ph.D. ’12) worked with a team to develop calibration technology for monitoring crop water usage while pursuing his Ph.D. in Horticultural Science. And Carl Jensen (M.S. ’14) started working on the problem of grain storage in Sub-Saharan Africa while obtaining his masters in International Agricultural Development. Each is enjoying the challenges of building a company from scratch but they’ve all had to be flexible as ideas met market realities.

An evolving method for turning waste into plastic

As an undergraduate in the Chemical Engineering program at UC Davis, John Bissell was convinced there had to be a better way to make plastic.

The majority of plastic in the world—from the reviled single-use shopping bag to your toothbrush—is derived from petroleum, a non-renewable resource. And a tremendous amount of petroleum goes into plastic: In the U.S. alone, 191 million barrels of hydrocarbon gas liquids (byproducts of petroleum refining) or about 2.7% of total U.S. petroleum consumption was used to make plastic in in 2010, when the U.S. Department of Energy last reported this data.

Instead of using petroleum, Bissell, along with fellow students Ryan Smith and Casey McGrath, found a way to make the base components of plastic using modified bacteria to digest a variety of waste products like sewage and agricultural waste. The concept was promising enough that the partners took out a patent for the bacteria and secured seed funding in 2008 to create Micromidas, Inc.

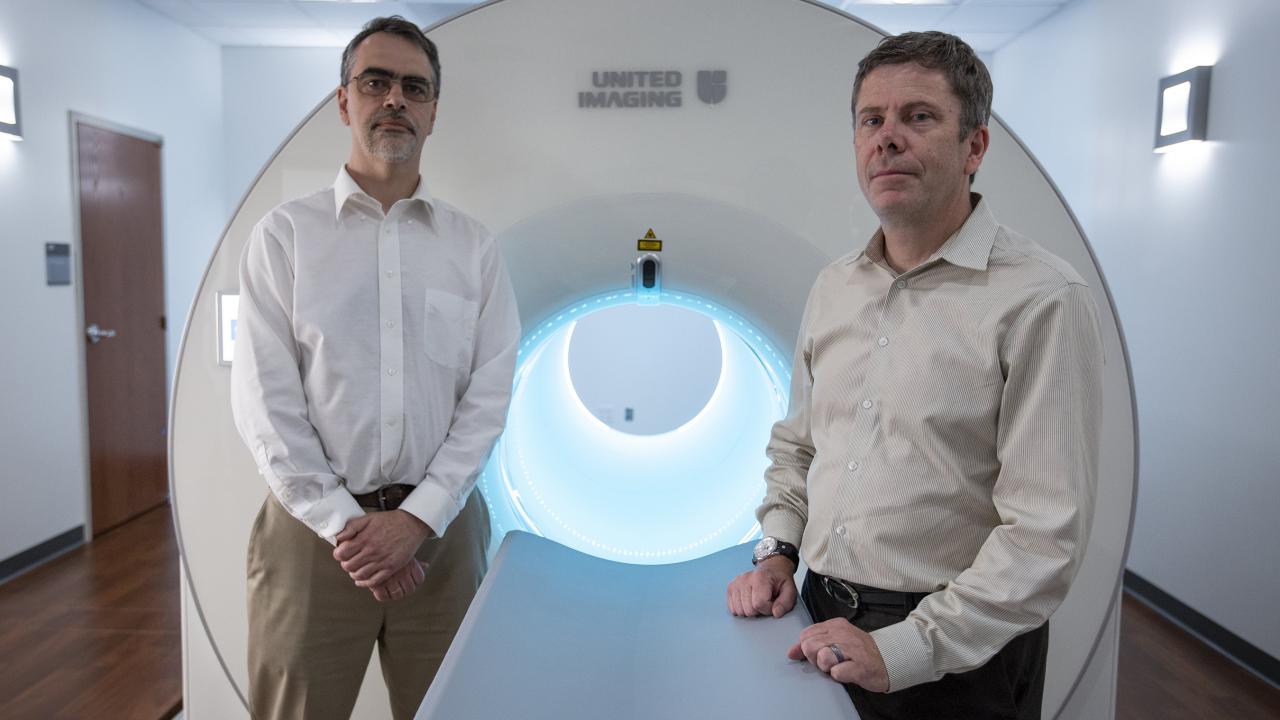

John Bissell, CEO of Micromidas, along with fellow UC Davis students Ryan Smith and Casey McGrath, found a way to make the base components of plastic from a variety of waste products including cardboard, rice hulls, and wheat straw. Bissell won the Cal Aggie Alumni Association’s Young Alumni Award in 2013.

One challenge with the bacterial process was it was not completely efficient. Bissell explains, “We had some indigestible things we couldn’t convert.” So in 2010 they looked for a solution that could augment the bacterial process and ended up finding an attractive way to convert the waste using a chemical process developed by Mark Mascal, a professor in the UC Davis Chemistry Department. The new process uses organic chemistry to convert biomass into monomers—the substituents of plastics. After weighing the benefits of both methods, Micromidas decided to shelve the original process using bacteria. Bissell says, “We could only pick one project at a time.”

When the small biorefinery in West Sacramento is going full-speed it can process about 200 pounds an hour of woody waste like cardboard, agricultural waste, wood chips, rice hulls, wheat straw, rice straw, bagasse and empty fruit bunches from palm oil processing.

By 2014, Micromidas had raised $25 million in venture capital to build a pilot-scale plant in West Sacramento, which currently employs about 25 full-time staff and 15 to 20 technical experts who consult part-time.

When the small biorefinery in West Sacramento is going full-speed it can process about 200 pounds an hour of woody waste like cardboard, agricultural waste, wood chips, rice hulls, wheat straw, rice straw, bagasse and empty fruit bunches from palm oil processing.

The next step for Micromidas is a larger refinery. Bissell explains, “We are providing access to a new class of material. I’d like to see the technology become an integral part of the existing chemical industry.”

Water conservation tool becomes increasingly more sophisticated

When Tom Shapland was pursing his master’s and Ph.D. in the College of Agriculture and Environmental Science there was technology—Surface Renewal—that could calculate water usage in fields but the calibration process required extremely expensive instrumentation, making precise measurements too expensive to be practical outside of academia.

“Irrigation is the single most important lever for influencing the outcome of the crop and for attaining the crop goal,” Shapland explained. So being able to accurately measure water could give California farmers an important tool to manage their water use efficiently.

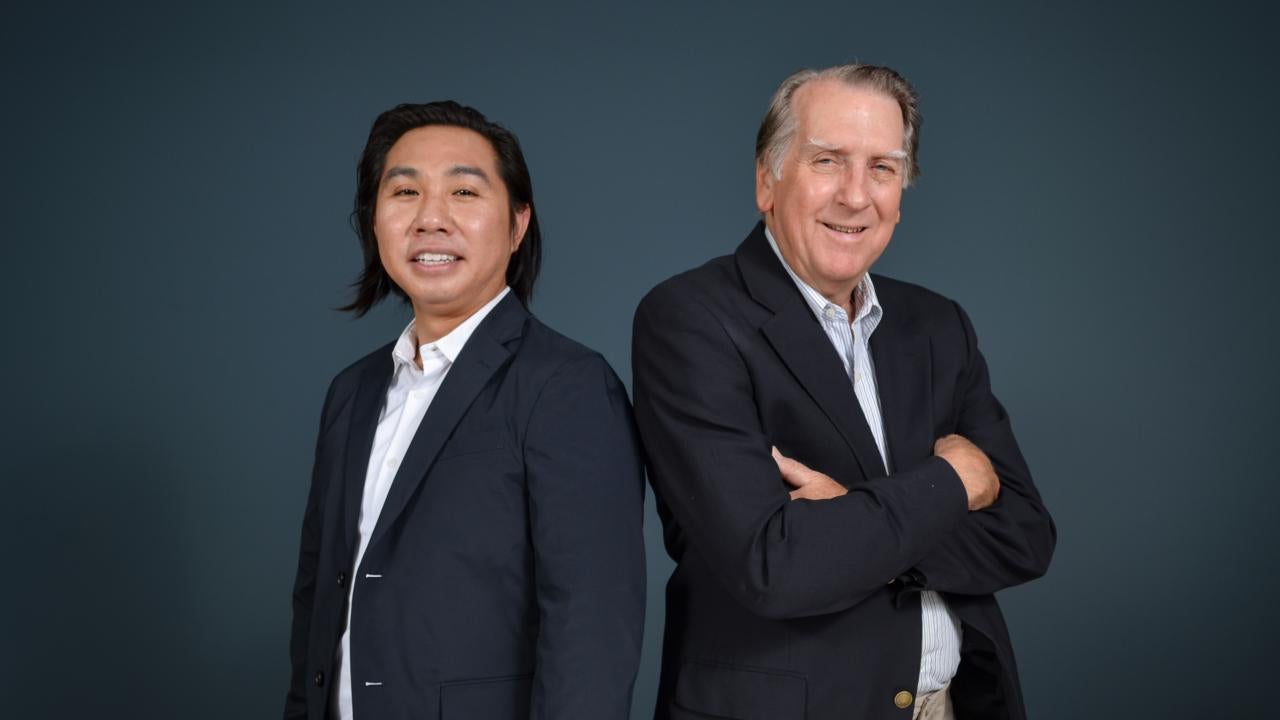

Tom Shapland, CEO of Tule, developed the technology while pursuing his Ph.D. in the College of Agriculture and Environmental Science.

Shapland tackled the challenge of making the technology affordable, working with his dissertation committee, which included Kyaw Tha Paw U, Rick Snyder and Andrew McElrone. Eventually, they came up with a solution for reducing the cost of the technology that forms the basis of Tule Technologies and in 2014, UC Davis’ Venture Catalyst helped the fledging company get started.

The Tule system uses sensors and a monitoring system above the crop canopy to tell growers precisely how much water their plants are using. Farmers access the data through a web dashboard or iPhone app. But as Tule Technologies developed growers wanted to fine-tune the irrigation, sometimes maximizing quantity, requiring more water, or maximizinge quality, which required putting the plants under a degree of water stress.

Tule Technologies is working with close to 300 California growers, mostly for wine grapes and almonds, with about 1,200 sensors in the fields. Farmers can access data through a web dashboard or iPhone app and can make irrigation decisions accordingly.

Tule Technologies is working with close to 300 California growers, mostly for wine grapes and almonds, with about 1,200 sensors in the fields. Farmers can access data through a web dashboard or iPhone app and can make irrigation decisions accordingly.

So Tule added features to the system to help growers reach their targeted stress levels. If the plants became too stressed—or not stressed enough—the technology alerts farmers, who can then make irrigation decisions accordingly.

Tule is growing and now has six employees and is looking for programmers interested in water conservation. It is working with close to 300 California growers, mostly for wine grapes and almonds, with about 1,200 sensors in the fields.

For Shapland the most rewarding aspect is utilizing and developing the technology, helping customers achieve their goals and conserve water and time. “I really love working with growers. Agriculture is complex. I learn a lot from them.”

Thinking outside the bag to help smallholder farmers in Africa

In Zambia, where farming is the country’s main livelihood, crop storage is a problem. Lacking adequate grain silos for staples like maize, a significant portion of each harvest is lost to vermin, insects, or molds that can create poisonous aflatoxins.

Carl Jensen became interested in working with smallholder farmers in Zambia—small farms usually supported by a single family growing a mixture of cash crops and subsistence farming— when he was part of an international team that studied the problem of storage. After graduating from UC Davis in 2014 he returned to Zambia to co-found Zasaka with Sunday Silungwe, whom he had met during a trip to Africa.

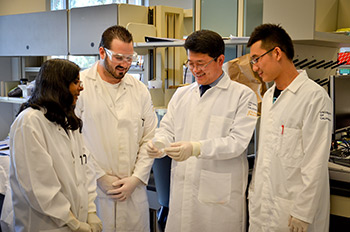

Zasaka co-founders (in blue t-shirts) Carl Jensen, left, and Sunday Silungwe, right, with a group of Private Extension Agents (PEAs). Jensen and Silungwe met in 2013 at the International Development Design Summit in Zambia. Silungwe, holds a degree in developmental studies from Zambia Catholic University and has worked in community development for many years.

Zasaka means “it’s in the bag” in the Zambian dialect of Nyanja, and selling bags—specifically the Purdue Improved Crop Storage (PICS) bag—made up a portion of the business plan to sell agricultural products and services to farmers. PICS bags are made of three layers of specialized plastic and can store more than 200 pounds of grain for up to a year. The idea was promising enough that Zasaka won both the People’s Choice award and the Ag and Food Innovation prize in the 2014 UC Davis Big Bang! Business Competition.

During the first year, Zasaka sold about 2,000 bags to farmers in Zambia at $2.50 each. But the price for the bags increased as the Zambian Kwacha became weaker against the U.S. dollar, creating a dilemma for the new enterprise.

“We kept trying to make it work, but we had to decide if we were a business or if we were going to subsidize the farmers,” said Jensen. Unable to cover the costs, they made the difficult decision to stop selling bags.

Anes Tembo, a Zasaka Private Extension Agents (PEA), stands in one of her farmer’s fields and displays cowpea nearly ready for harvest. The farmer is set to harvest more than half a ton of cowpea seed from which she will double her annual income. Each PEA provides agronomic and financial management training to a cohort of 40 farmers, overseeing their loans and aggregating final products for sale to Zasaka.

But Zasaka’s model had always included more than just bags, so the young company turned its attention to legume seeds like cowpeas—buying, packaging and selling them to farmers, sometimes directly and sometimes through the government and non-governmental organizations.

“We intend to be the leading seed company in our sector by volume and quality. The goal is to raise incomes of tens of thousands of farmers through direct production relationships while increasing the availability of legumes to farmers across the region,” said Jensen. He notes that this year Zasaka will process and package 440,000 pounds of seed produced by 400 farmers.

A group of farmers attends a training led by a field supervisor at Zasaka’s base of operations, the POD.

The company also delivers training—farmers who have worked with Zasaka have seen increases in maize yields of 75 percent. Zasaka now employs 9 full-time people and is expanding this May to reach 2,000 farmers under the supervision of 50 Private Extension Agents (PEAS) dedicated to answering their questions on agronomy and farm management.

During an interview from Chipata, Zambia, Jensen described the tremendous satisfaction he feels from the work he is doing. “We are about two months out from harvest now. Everywhere you look you see full fields and the bounty to come.”

semi-dwarf Hard Red Spring variety, which offers a high-yielding plant and a resulting grain with high protein content and excellent bread-making quality. This variety is resistant to current races of stripe rust disease and is well adapted to the Sacramento, San Joaquin and Imperial Valleys in California.

semi-dwarf Hard Red Spring variety, which offers a high-yielding plant and a resulting grain with high protein content and excellent bread-making quality. This variety is resistant to current races of stripe rust disease and is well adapted to the Sacramento, San Joaquin and Imperial Valleys in California.